Almost all of us have heard of the electric eel. But did you know that other animals also use electricity in some

form, whether producing or sensing it?

Many land animals have sensory organs that can detect electrical fields, including some insects such as bumblebees.

They use them to either locate prey or to communicate. However, only those animals that live underwater can generate electricity themselves. There are about 400 species of fish that use electricity. No doubt others will be discovered in the future. We’ll list some of the more interesting ones.

Electric Eel

This is not an eel but a species of knife fish. They all live in the Amazon River basin. There are now three known species, one of which can generate up to 850 volts of electricity in a single discharge.

These fish have three organs that work together to generate electricity. These organs take up four-fifths of the fish’s body, which is sizable because these fish can grow up to eight feet long.

While it’s rare for a shock from an electric eel to be fatal, it can happen. It can also cause permanent disabilities.

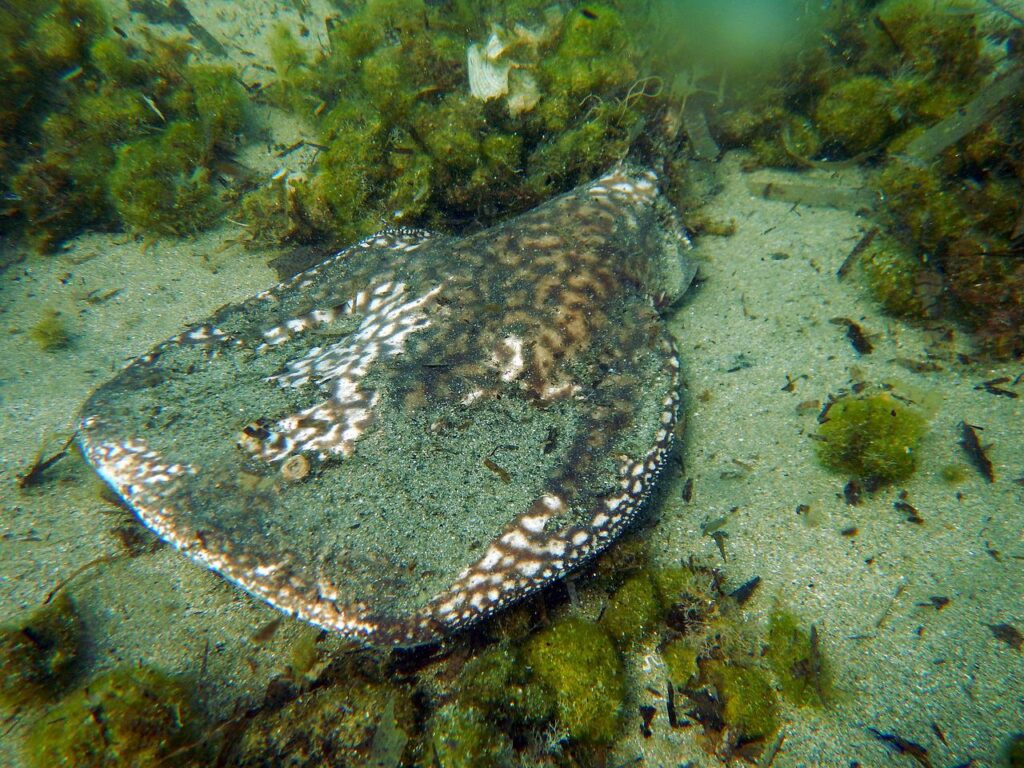

Electric Skate

This is a kind of ray fish, also called a torpedo ray. They live in shallow coastal waters. They can produce shocks of up to 200 volts to stun prey or ward off predators.

This ability was discovered in ancient times. Ancient Greeks and Romans used these rays to sedate people during surgery. They also used them to treat various ailments such as migraines.

Electric Catfish

No, this is not the name of a rock band, but a catfish species that lives in tropical Africa, including the Nile River. It can generate up to 350 volts to stun prey. Of course, it can use these shocks in defense as well.

Like other fish that generate larger shocks, much of the fish’s body contains electricity-producing cells. Animals that generate weaker currents usually just have a specialized organ in the tail.

Peters’s Elephantnose Fish

This is an aptly named fish due to the very unusual snout. This fish, which lives in West and Central Africa’s fresh waters, produces a weak charge. Unlike the fish that produce more powerful shocks, this fish uses its abilities to communicate and navigate. This is important as the waters they live in are very cloudy with sediment, making for very poor visibility.

The fish sends out weak electrical signals. When something nearby interrupts these signals, receptors on the fish tell it that something is there. Other similar fish recognize these signals, enabling communication.

Black Ghost Knifefish

A relative of the so-called electric eel, these fish live in the Amazon basin but also other fresh waters in South America. It’s all black except for two rings on the tail and a white streak on the nose. It grows to almost 20 inches long.

It produces weak electric signals but can also receive them. It uses these talents to locate its favorite food, insect larvae. It also serves as a location device and helps them communicate with other such fish.

They sometimes produce voltage while mating.

Northern Stargazer

This fish is named because its eyes are near the top of its head. Its mouth also points upward, allowing the fish to hide in the sand, waiting for prey to swim over it. It can stun the prey with electricity produced by modified eye muscles, then grab it with that upturned mouth.

This fish lives along the eastern shores of the United States, all the way between North Carolina and New York.

Oriental Hornet

This hornet has a unique ability when it comes to electricity. It has special yellow tissues that absorb sunlight. It also has brown tissues that generate electricity, which it uses as a power source. This means that it converts sunlight into energy.

It’s the only known animal that can do this. Scientists discovered this when wondering why the insects are most lively when the sun is strong, which is unusual. In effect, these insects have built-in solar panels.

Animals That Use Electricity

These animals don’t produce electricity, but they can sense electrical fields. These include mammals and even insects.

Shark

Sharks are equipped with electric receptors in their snouts. These can detect weak electrical fields produced by the muscle movement of prey animals, telling the shark if a nearby animal is wounded, for instance.

Some scientists believe that sharks can navigate over long distances by sensing the Earth’s magnetic field with these receptors.

Guiana Dolphin

This is the only marine mammal to detect prey by sensing their electrical fields. They are born with small whiskers on their snouts. These fall off after a time, leaving pits sensitive to electric fields.

They need this talent, as the waters they live in on the western Atlantic coast of South and Central America provide cloudy visibility.

Platypus

This is the Australian mammal that looks as though it were made from pieces of other animals. It has a beaver-like coat, webbed feet with claws, and a soft duck-shaped bill. In this bill are 40,000 receptors that pick up electrical signals in the water. It moves the bill back and forth in water over the bottom, using the receptors like a metal detector to find food hiding in the sand.

Echidna

This is another Australian animal. It looks like a small, spiny anteater with a narrow, flexible snout. This snout contains receptors to locate ants and termites. It may be the only land animal that locates prey this way.

To make it even more unusual, it and the platypus are the only mammals that lay eggs.

Bumblebee

These ground-dwelling bees have the unique ability to change the natural electrical charge around a flower.

The rapid beat of the wings creates an electrical field for a minute and a half, telling other bees that this flower has already been raided.

There are other ways animals use electrical charges, from geckos that use static electricity to help them climb up smooth surfaces like glass to spiders that use web glue that attracts electrically charged particles, including those produced by flying insects.

This causes the web actually to move toward a nearby insect. Scientists continue to discover how animals use electricity and electrical charges. Who knows what they’ll discover next?